The Power of Tarantula Venom

Tarantulas, the large and often hairy spiders, are a source of both fascination and fear. While their size and appearance can be intimidating, it’s their venom that truly captures scientific interest. Tarantula venom is a complex cocktail of toxins, each with a unique effect on the body. This intricate mixture is not merely a defensive tool, but a sophisticated weapon designed to immobilize prey. Understanding the components of this venom provides valuable insights into the spider’s hunting strategies, potential medical applications, and the overall biology of these fascinating creatures. The composition of tarantula venom varies between species, making each venom profile unique and presenting a diverse area of study for scientists.

Toxins 1 — Pain-Inducing Compounds

Pain-inducing compounds are a primary component of tarantula venom, playing a key role in deterring predators and incapacitating prey. These toxins trigger immediate and intense pain sensations, often causing localized discomfort around the bite site. This rapid response is essential for the spider’s survival, as it quickly discourages further attacks. These compounds interact with pain receptors, such as TRPV1, found throughout the body. This interaction sends immediate signals to the brain, resulting in the sensation of sharp, burning pain. The intensity can vary depending on the species and the amount of venom injected, but the primary effect is always immediate distress. The composition of these compounds varies between species, yet their function remains consistent — to inflict a quick and effective defense mechanism.

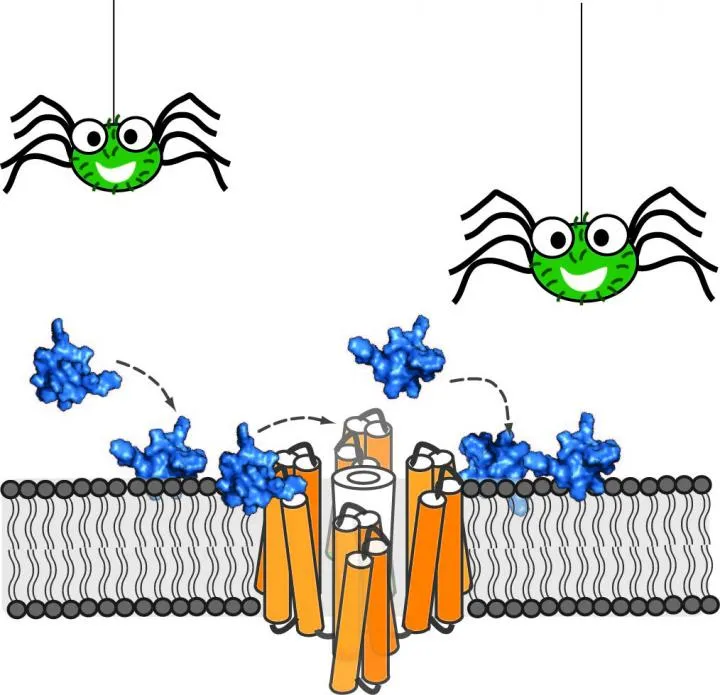

How These Toxins Work

The pain-inducing compounds found in tarantula venom primarily target the body’s pain receptors. These receptors, especially TRPV1, are activated by heat, acids, and certain chemicals. When the venom toxins bind to these receptors, they cause a cascade of signals to be sent to the brain, registering as pain. This process happens almost instantly after the bite, creating an immediate defense that can startle or deter predators. These toxins often mimic the action of other pain-causing agents, amplifying the signals and making the pain more intense. Scientists are actively studying these compounds to better understand pain mechanisms and potential treatments, as the mechanisms behind the actions of these toxins could give clues to new methods of pain management in humans.

Symptoms of a Bite

The symptoms of a tarantula bite are often characterized by immediate and intense pain at the site of the bite, which can be followed by redness, swelling, and itching. Muscle cramps and stiffness can also occur, and in some cases, there may be nausea and vomiting. While fatalities are extremely rare, some individuals may experience allergic reactions. For those with a high sensitivity or pre-existing conditions, it is always advised to seek medical attention to assess and treat any potential serious reactions. The severity of the symptoms varies based on the species of tarantula, the amount of venom injected, and the individual’s sensitivity. Proper medical attention can help provide relief and prevent complications.

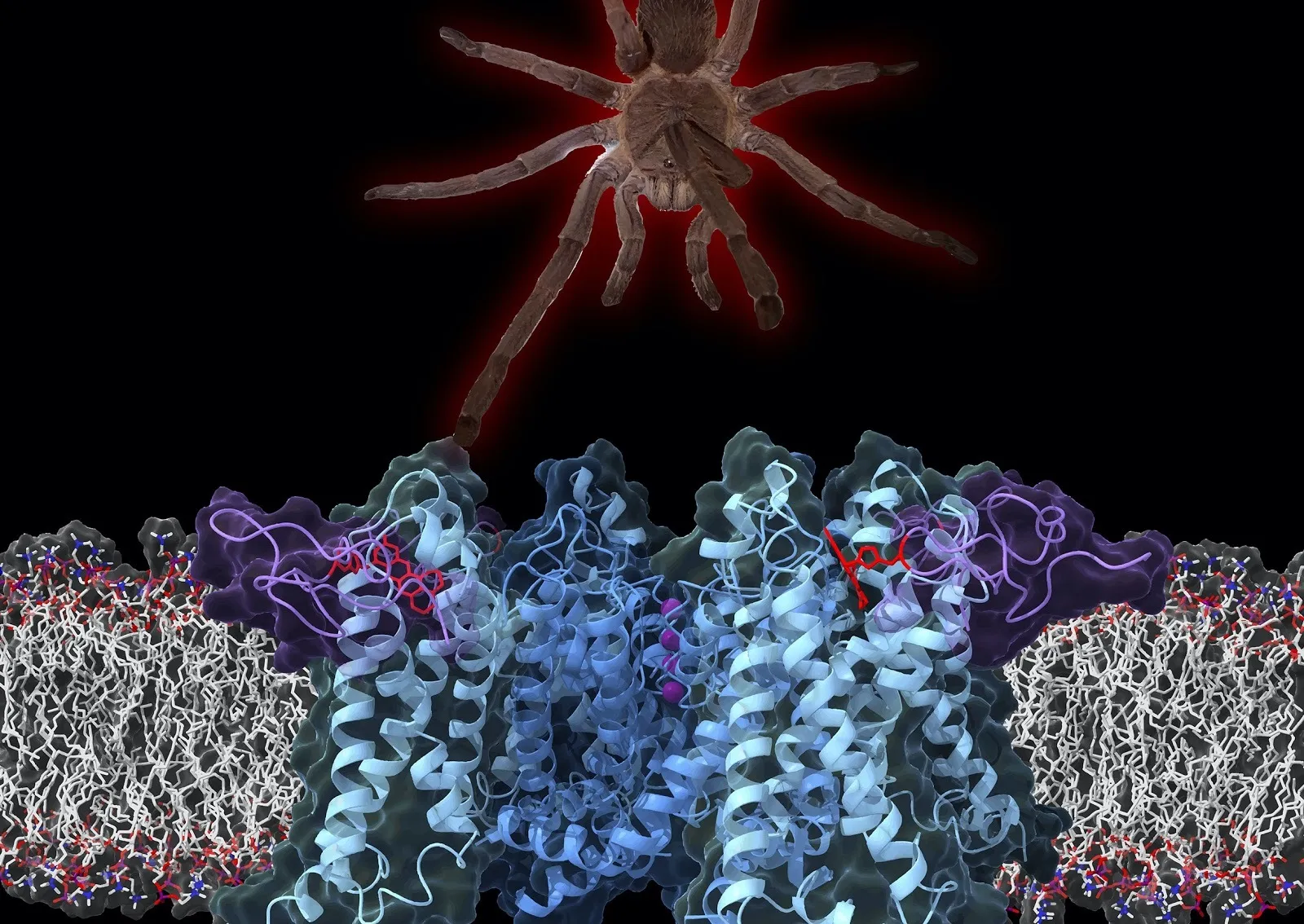

Toxins 2 — Neurotoxins

Neurotoxins represent a vital component of tarantula venom, designed to interfere with the nervous system of the prey. These toxins disrupt the normal transmission of nerve signals, leading to paralysis, muscle spasms, and other neurological effects. By interfering with the function of nerves and synapses, neurotoxins immobilize prey, making it easier for the tarantula to capture and consume. This class of toxins is highly specific, often targeting particular ion channels or receptors in nerve cells. They are capable of causing a wide range of effects, from mild discomfort to severe paralysis. Their action is crucial for the survival of the spider, ensuring that prey is effectively subdued.

Impact on the Nervous System

Neurotoxins profoundly impact the nervous system by disrupting the delicate balance of ion channels and neurotransmitters. These toxins can block or overstimulate nerve signals, leading to a variety of neurological symptoms. The effect of the neurotoxins causes the disruption of the nerve’s ability to send and receive signals correctly. This interference can result in muscle spasms, paralysis, or other neurological dysfunctions. The type of effect depends on the specific neurotoxin and the specific components of the nervous system it targets. Because the nervous system is so important for all bodily functions, disruptions can have far-reaching and often debilitating effects on the victim.

Types of Neurotoxins

Tarantula venom contains a diverse array of neurotoxins, each with a unique mechanism of action. Some neurotoxins target sodium channels, disrupting the flow of ions and interfering with nerve impulse transmission. Others affect potassium channels, leading to similar neurological effects. Certain neurotoxins also target the receptors of neurotransmitters, such as acetylcholine, causing overstimulation or blocking nerve signals. The specific type of neurotoxin and its concentration varies among different tarantula species, resulting in the varied effects observed in victims. The study of these neurotoxins is crucial for understanding how they interact with the nervous system and for potentially developing new treatments for neurological disorders.

Toxins 3 — Enzymes

Enzymes, another key component of tarantula venom, serve primarily to break down tissues and aid in digestion. These biological catalysts accelerate the breakdown of proteins, fats, and other complex molecules, facilitating the spider’s ability to consume its prey. Enzymes can also play a role in spreading the venom throughout the victim’s body, increasing its effectiveness. The types of enzymes in tarantula venom vary, but they all contribute to the overall effectiveness of the venomous cocktail, both in the breakdown of tissues and in the disabling of the prey. The presence of these enzymes is a vital aspect of the spider’s predatory strategy, ensuring efficient nutrient acquisition.

Enzymatic Activity Explained

Enzymes in tarantula venom catalyze biochemical reactions, breaking down complex molecules into simpler substances. Proteases, a common type of enzyme, break down proteins into smaller peptides and amino acids. Lipases break down fats. The specific enzymes present and the rates at which they operate determine the venom’s overall effects. This enzymatic activity is crucial for the spider to digest its prey externally, enabling the absorption of nutrients. The efficiency and specificity of these enzymes ensure that the spider can effectively convert its prey into usable food. The study of these enzymes has a broad impact, leading to a better understanding of biological processes.

Effects on Tissue

The enzymes in tarantula venom have significant effects on the tissues of the bitten organism. Proteases and other enzymes break down the tissues, causing damage and facilitating the venom’s spread. This breakdown can cause local inflammation, swelling, and pain. The tissue damage assists in the digestion process, allowing the spider to feed. The extent of the damage depends on the concentration and type of enzymes in the venom, along with the victim’s overall health and sensitivity. These localized effects help the tarantula to subdue and consume its prey efficiently.

Toxins 4 — Protease Inhibitors

Protease inhibitors are a surprising component of tarantula venom, which function to counteract the activity of proteases. They are responsible for preventing the breakdown of proteins by inhibiting the action of proteases. These inhibitors can protect the spider from autodigestion, which prevents the spider from digesting itself. These inhibitors also help in maintaining the venom’s effectiveness by controlling the enzymatic activity. This dual role makes protease inhibitors an essential component of the venom, ensuring that the venom acts as a potent and effective agent for the spider’s defense.

Function in the Venom

Protease inhibitors play a critical role in regulating the overall function of tarantula venom. They prevent the excessive degradation of the venom components. The presence of these inhibitors maintains the stability and activity of the venom, ensuring that it remains effective over time. This regulation is a crucial part of the spider’s survival strategy. They modulate the overall toxicity of the venom, by balancing the activity of the venom’s other components. The activity of protease inhibitors help to make sure the venom is effective, and is always ready to be used, making them an essential component in a spider’s survival.

Role in Defense

In addition to regulating venom function, protease inhibitors also play a role in the spider’s defense. These inhibitors help to protect the spider from being digested by its prey. They are responsible for protecting the spider’s own tissues from self-digestion. This defense mechanism allows the spider to survive and capture its prey with minimal risk to itself. The strategic use of protease inhibitors highlights the complex and sophisticated nature of tarantula venom, which includes a variety of components that play a number of roles in the spider’s survival.

Toxins 5 — Histamine-Releasing Factors

Histamine-releasing factors are another important component of tarantula venom, which cause the release of histamine in the body. Histamine is a compound that causes inflammation, itching, and other allergic-like reactions. This release can cause localized swelling, redness, and sometimes more generalized symptoms. These factors are a key part of the venom’s effects. The release of histamine contributes to the immediate discomfort and distress experienced by the bitten organism. The role of histamine-releasing factors indicates the versatility of tarantula venom, which can induce multiple and varied effects to enhance its predatory or defensive function.

Histamine’s Role

Histamine, when released in the body, causes a variety of physiological effects, primarily related to inflammation. It causes the dilation of blood vessels, leading to increased blood flow and the redness and swelling commonly associated with allergic reactions. Histamine also increases the permeability of blood vessels, allowing fluid to leak into the surrounding tissues, resulting in swelling. These effects serve a defensive function, by attracting immune cells to the bite site. The release of histamine causes immediate effects that amplify the pain, which contributes to the overall effectiveness of the venom.

Allergic Reactions

Some individuals may experience allergic reactions to tarantula venom, which is mostly caused by the histamine-releasing factors. Symptoms can range from mild skin irritation to more severe reactions like difficulty breathing or anaphylaxis. Those at higher risk of allergic reactions include individuals with a history of allergies or those with a heightened sensitivity to insect venom. Medical attention is always required to treat severe allergic reactions, which include the administration of antihistamines, epinephrine, or other supportive care. Understanding the role of histamine-releasing factors and allergic reactions is essential to managing the risks associated with tarantula bites, ensuring that any potential complications are addressed promptly and effectively.

Conclusion

Tarantula venom is a complex and fascinating mixture of toxins, each with its own specific effects. From pain-inducing compounds and neurotoxins to enzymes, protease inhibitors, and histamine-releasing factors, these components work together to incapacitate prey and deter predators. Understanding the diverse functions of these toxins provides valuable insights into the spiders’ hunting strategies and defensive mechanisms. As research continues, it is possible that tarantula venom could be used in medicine, revealing its potential therapeutic applications. These are a testament to the sophistication of the natural world and the unique strategies that have evolved for survival. The study of tarantula venom highlights the importance of understanding the many complexities of biology and the world around us.